The other day I was wandering lost in a Target Superstore, looking for one of those trivial items, like the darning needle that used to be sold locally until all the big box stores sucked the local sundry shops dry. I found myself in the game aisle, and spotted the three board games that were a staple of my childhood – Monopoly, Risk and the Game of Life. I hadn’t played any of them for years, and I wondered what subliminal messages these board games sent, all in the name of family fun.

I never liked Risk, and in fact I think that it was a game that only guys played. It involved world domination based on dice rolls, and the number of dice you rolled depended on the size of your army. There was no role for diplomacy and negotiation, it was all out warfare from beginning to end. The armies were represented by plastic game pieces, obscuring the fact that thousands of men could be demolished in a single battle, and perhaps I found this disconcerting. Additionally, I grew up during the cold war of the 1960s, and the game board graphically illustrated the enormity of the USSR, which was divvied up into territories with odd names such as Irkutsk and Yakutsk. Somehow Russia just seemed too menacing and nerve wracking, as if it could crush the puny United States with a single roll of the dice.

Monopoly was an enduring family favorite, and it was a rite of passage to teach our children how to play. My strategy was always to try and get a monopoly on the really inexpensive properties – like Connecticut (the light blues) and Mediterranean (the purple  ones) and then immediately throw up cheap hotels. Accumulation of wealth was the goal, and in a zero sum game, it always came at the expense of the other players who landed on your properties. Although not the best message to send to impressionable minds, it was still somewhat satisfying to methodically grind opponents into dust and emerge victorious. However, I do admit my strategy of being a low rent landlord on the blues and purples was rarely successful.

ones) and then immediately throw up cheap hotels. Accumulation of wealth was the goal, and in a zero sum game, it always came at the expense of the other players who landed on your properties. Although not the best message to send to impressionable minds, it was still somewhat satisfying to methodically grind opponents into dust and emerge victorious. However, I do admit my strategy of being a low rent landlord on the blues and purples was rarely successful.

The Game of Life – this was a kinder, gentler game. You started this game in a little plastic car, where you could put either a pink or blue peg. Along the way you could get married and have children, adding the appropriate colored pegs to fill up your car. I think I liked this game because it made life seem so simple and reflected my view of a secure mainstream life consisting of getting married, having a job and children. In about 45 minutes you “retired” and the person with the most money was the winner. As I looked at the game on the Target shelf, I wondered if the Game of Life had been updated over the past 50 years. Is it still sending the message that accumulation of wealth is the key goal in life? I popped the game into my cart and thought it might be interesting for someone with a little life experience of her own to play the Game of Life.

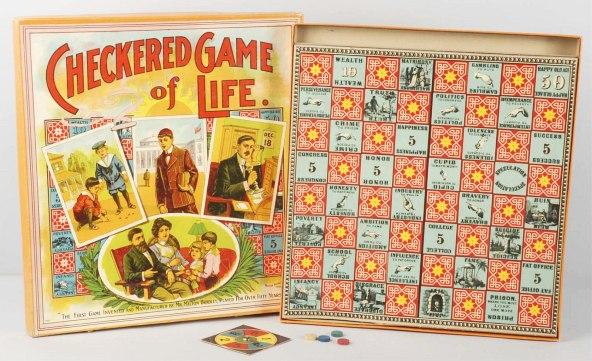

Once home, I did a little research on the game and its inventor, Milton Bradley. In the 1860’s Bradley was a lithographer, and his hopes for a quick fortune were dashed when he

created a lithograph of a clean-shaven Lincoln, who then promptly grew his iconic beard. Bradley turned to board games, and his first game was called “The Checkered Game of Life.”

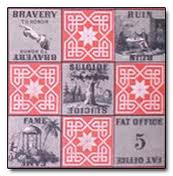

In fact, the 1960’s version of the Game of Life was supposed to be the 100th year anniversary of the game. However, the original Checkered Game of Life was entirely different. Bradley’s version was basically a variant of chutes and ladders as you moved through life’s challenges. And success in Bradley’s version was all about virtue triumphing over vice. For example, gambling was considered amoral, so Bradley’s game came equipped with a six sided top that was used instead of dice, since dice were associated with gambling. Squares such as Honesty, Bravery, Perseverance, Cupidity represented the ladders sending you upward to things like Happiness, Honor, Success and Matrimony, respectively. Chutes included such things as Idleness, which sent you down to Disgrace, Intemperance sent you down to Poverty and Gambling sent you to Ruin, depicted as a shadowy debt collector at the door. No money changed hands and you weren’t out to screw the other players. Instead you earned points for your virtues, and the first person to get 100 points won. Even though the game was supposed to “forcibly impress upon the minds of youth the great moral principles of virtue and vice” it could be brutal. There was a  horrifying square labeled “Suicide,” illustrating some poor soul hanging from a tree. The current Game of Life is also promoted as a “family game,” and the 1960 version was “heartily endorsed by Art Linkletter,” a genial TV and radio host who presumably knew that good, wholesome family fun was all about money. His face even appeared on the $10,000 bill.

horrifying square labeled “Suicide,” illustrating some poor soul hanging from a tree. The current Game of Life is also promoted as a “family game,” and the 1960 version was “heartily endorsed by Art Linkletter,” a genial TV and radio host who presumably knew that good, wholesome family fun was all about money. His face even appeared on the $10,000 bill.

I convinced Frances to play the Game of Life that I had just bought, and then over the next several weeks, I managed to find three prior versions, for comparison purposes, unearthed from friends’ dusty game closets – a vintage 1960s version, a 1980s version and a 1990s

version. The first thing Frances said was, “I don’t like the pink and blue people pegs. I reject the gender binary since sexuality lies along a spectrum.” This pronouncement would probably have sent the conservative Milton straight to the suicide square. The next big issue, unchanged over the past 50 years, was that all players must stop in front of a white New Englandy looking church and get married. No exceptions, everyone has to get married, which left both Frances and I grumbling. However, I pointed out, that in a stunning display of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” the game lets you marry a same sex partner. Frances happily put two blue pegs in her car in support of LGBTQ community and off we went.

Early on, you have to choose whether you will go to college or start a career, and each successive version of Life has attempted to be more realistic by increasing the cost of college tuition. It is currently $100,000 up from $1,500 in 1960. Once you complete college, you simply pull a career card out of the deck. My big complaint is that there is no mention of whether the job offers health benefits. If you really want a jolt of reality, players should be forced to choose between a high paying job without health benefits, and a lower paying job with health benefits, with subsequent squares representing various health issues that would really drain you financially. Maybe you could even land on a space that assigned you some really expensive pre-existing condition, like psoriasis or lumbago, which would double or triple any health bill. This important teachable moment is tragically ignored in this Game of Life.

The spouse is basically a nonentity in this game, just along for the ride. One of the gameboards shows a man and women walking together both wearing suits and carrying briefcases, but there is no mention of whether the spouse works, and no opportunity for a dual income. Both Nick and I have had several career changes, and have always appreciated the safety net of two incomes. Even though you can get fired in this game, there are no consequences, and thus no need to depend on your spouse. You simply draw another career card from the deck, and presto, you’re back in business. Finally, there is no square that says, “Divorce! Impoverish Your Family!! Cut your pay check in half!!”

Family planning is non-existent in the Game of Life, and the instructions say that if you cannot fit any more pegs in your car, “Just crowd them in as you do in real life,” which is pretty much what my parents did. Bizarrely, it turns out that having children is a money maker. With each birth everyone has to give you a cash gift, and there are very few squares that ding you for child care costs – you could sail through the entire game without ever spending a dime on your children – no daycare, no camp, no orthodontist, no college, no nothing. And then even better, when you get to the end of the game, the bank forks over $20,000 for each child in the 1960s version, increasing to $48,000 in the 1980s version. For some reason, in the current version, the baby bounty has been has been reduced to a measly $10,000.

As Frances and I played the game, the general impression was that money just showered down upon us – there are cash prizes for such things as discovering Atlantis while skin diving, climbing Mt.Everest, or winning a tennis tournament, all very elitist activeness in and of themselves. The more recent versions make an effort to include more socially redeeming squares, but this is just a big money laundering scheme. For example, if you “help the homeless” the bank will reward you $40,000, another twenty grand for “saying no to drugs,” and fifty grand just for voting. In the current version, instead of showing a model white family actually playing the game, the box top shows a cartoon of a raucous family who are apparently just throwing money out the car window. Art Linkletter is no longer on the money, but the $5,000 bill shows a baby with blocks with the dollar symbol on them, the $10,000 bill has a boy catching a baseball with a dollar sign on it, and the $50,000 shows a man holding a golf ball with a money sign on it. The man on these bills is very interesting, since he is the only person of color in the whole game, but it is impossible to tell if he is African American, Indian or whatever.

family who are apparently just throwing money out the car window. Art Linkletter is no longer on the money, but the $5,000 bill shows a baby with blocks with the dollar symbol on them, the $10,000 bill has a boy catching a baseball with a dollar sign on it, and the $50,000 shows a man holding a golf ball with a money sign on it. The man on these bills is very interesting, since he is the only person of color in the whole game, but it is impossible to tell if he is African American, Indian or whatever.

Milton Bradley thought gambling sent you straight to ruin, but the new versions are all about gambling, from betting on a simple spin of the wheel, stock markets or long term investments. At the end of the game, you reach the Day of Reckoning, which Bradley would have certainly approved of, but then would have been devastated to know that the reckoning does not involve truth, honor or happiness. Players are offered one last chance to gamble all their assets on a single spin in a desperate bid to be an instant winner. My cousin Ned suggested that if the game were more true to life, the spinner would be metallic and people could secretly acquire magnets representing insider trading, which could be strategically placed to influence the spinner in their favor.

If you lose the last “winner take all” gamble, you are sent straight to the Poor Farm. But if you have enough sense to decline this gamble, you just keep going to Millionaire Acres, wait for everyone else to finish, and then count your money. The one with most money wins, but I can’t remember anybody caring – Frances and I certainly didn’t. You could be happy enough to be one of the many millionaires in Millionaire Acres, just not the top millionaire. In the 1980s version, the Poor Farm was replaced with “Bankruptcy,” but even this seemed pleasant enough, since the square also noted anyone who was bankrupt could “retire to the country and become a philosopher.” The American Society of Philosophers probably rose up in righteous indignation at this pronouncement, and by the next version, the options at the end of the game were retirement at the more downscale Countryside Acres or the elite Millionaire Acres. The humiliation of a Poor Farm or Bankruptcy was eliminated. Life was definitely very cushy, dreamy and downright delusional.

As we finished up the game, both Frances and I agreed that we could never imagine playing the Game of Life again. However, I do see real potential in Milton Bradley’s original Checkered Game of Life version, which focuses on points instead of money. I would immediately take out the Suicide square, perhaps replace with a Depression square and indicate that players would continue to lose turns until they recovered by “rolling” a certain number on the spinner. I would then update some of Bradley’s virtues and vices, perhaps swapping out the virtue of “Matrimony” for something more relevant like “Reduce Carbon Footprint,” or identify “Wall Street Banker” as a vice that sends you tumbling straight down to “Disgrace.”

The missing words in the following poem are anagrams (i.e. share the same letters like spot, post, stop) and the number of asterisks indicates the number of letters. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for answers.

Milton Bradley wanted people to **** a life of truth and virtue

So his Checkered Game of Life was designed to educate and alert you

To the **** of vices like crime or idleness – you’d better beware

Or you’ll be sent down to poverty, ruin or even the suicide square.

Avoid intemperance, it could **** your judgment and lead to a bad decision

And send you down to poverty, disgrace or even prison.

And Bradley considered gambling the most **** vice

So he insisted on using a spinner instead of the gambler’s dice.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Answers: live, evil, veil, vile

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: