Between Christmas and New Year’s our family traditionally gathers at our cabin in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP) along the shores of Lake Superior. Several other families have the same tradition, and therefore New Year’s has been celebrated with the same group of family friends over many decades and generations. This little community is extraordinarily tight. The cabins are isolated beyond the reach of cell phone, there is no TV and the days are short, with the sun setting by 4:30 PM. So there is much communal time in the cabins, and evenings are filled with a variety of quirky parlor games, so ingrained in tradition that I have never given them a second thought. However, this year I put myself in the shoes of a newcomer stumbling unprepared into this odd little enclave, thrust into a raucous living room on a cold dark night with no escape. I realize now that no matter how genial and welcoming this cozy group is, outsiders are roped into the medley of games and cannot help but think that they are being subjected to a series of institutionalized assaults on their personal space.

The first game is called Boston. Everyone sits in a chair in a circle, with one person blindfolded in the middle. He calls out some sort of category, such as “everyone who is wearing glasses,” or more pointedly, “anyone who voted for George Bush,” and those people have to get up and switch seats. Meanwhile the poor sap in the middle flails around trying to catch someone. Once he grabs someone, he gets three “feels” to guess who the person is. If you are caught you can usually maneuver yourself so that the “feels” hit something harmless like your arm. Sometimes other bystanders will leap to your aid by offering decoy hats or glasses. Everyone is too polite to grope for the goodies, but still …

I have not been to the UP for several years and was horrified to hear that the game Pass the Orange has been added to the mix. This one really put me over the top in terms of the personal space issue – you may remember this game when you were a giggly teenager in a basement rec room. Now on New Year’s Eve it has been resuscitated as a fun multigenerational family game. The group is divided into several teams arranged in a line. The first person puts the orange between his chin and neck, and then he must pass the orange to the chin and neck of the next person without using his hands. This maneuver requires a major body clinch, complete with rubbing between the two players as the orange gets loose and wanders around your chest – a thoroughly unappealing process unless you can hand pick your partner. Anyone wanting a refresher on Pass the Orange is referred to the movie Charade, starring Cary Grant and Audrey Hepburn. Cary Grant is challenged with retrieving the orange from the fleshy neck of a mammiferous and dowdy women. He approaches the woman with respect, but then realizes that there is no solution except for the full-on body press, mashing her breasts in the process. Serious personal space issues.

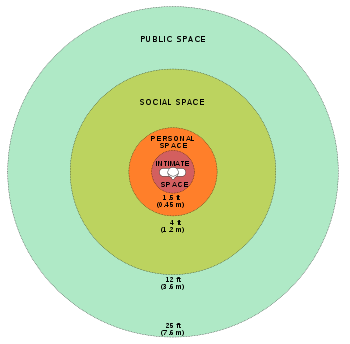

The spectre of every having to play Pass the Orange prompted me to consider the whole concept of personal space. The formal name of the field is called proxemics, founded by the anthropologist Edward Hall in the 1960s. He identified three different zones. First there is the intimate space (aka the pass the orange space) measuring from 0-18 inches. This proximity permits access to sensory input other than visual, i.e. full-on touch, smell and body heat. The next is the personal space, measuring from 1-4 feet. Hall envisioned the personal space as a small protective sphere, permitting a welcoming handshake, but also the possibility of domination by grabbing somebody by the arms. In cultures where bowing is the normal greeting, the personal space is a tad wider to prevent head konking. Beyond the personal space is the social space, measuring 4-12 feet, a large enough distance such that nobody expects to be touched, but close enough for conversation. Finally there is the public space of 12 feet or more, a distance where somebody could take evasive action if threatened.

Once defined, I realize that I can easily perceive the transition between these zones. When conversing in a crowded room, I definitely feel I am crossing barriers as I lean my head from the social into the personal space, and then it is somewhat uncomfortable if I need to dip my head further into the intimate space in order to be heard. We recently bought new porch furniture and were pleased to think that 8 people could comfortably sit on our porch based on two easy chairs and 2 three seater sofas. The saleslady pointed out that people never want to sit three to a couch – the function of the middle seat is to create the optimal personal space. I thought that this was a ridiculous notion until I saw guests pulling over an uncomfortable wooden chair instead of taking a vacant middle seat.

Hall pointed out that his measurements applied mostly to Americans, and the dimensions of the different spaces may depend on social settings and cultural backgrounds. For example, the dimensions of personal space tend to be smaller in Asian countries and more generally in any densely populated setting. In contrast, affluent people tend to demand greater personal space. Of course, all the rules are broken if you are in a crowded bus or train. At this point, Americans try to deny the enforced intimacy by staring off into the distance and not acknowledging that they are plastered up against someone. People also consider an overheard telephone conversation an invasion of personal space, most noticeable on a noisy train where the person sitting next to you is yelling over the ambient noise. The last time I was on the commuter train, I noticed that they had designated some cars as “quiet cars” where cell phones were not permitted.

It turns out that observing behavior in an elevator provides an interesting insight into cultural norms of personal space. In the United States, everyone enters the elevator and immediately turns and silently faces the elevator door. Women put their purses in front of them in a protective pose. It would be an interesting experiment to enter the elevator and turn and face everyone and watch the nervous energy mount. In contrast, Asians, in general, actually seek to diminish personal space by deliberately standing right next to you in an elevator even if there is plenty of space. Same thing in a public bathroom – supposedly Asians will select the stall next to yours even if there are rows of unoccupied ones. Our son Ned lives in China and experiences the diminished personal space on a daily basis. People tend to bunch together in lines well within the intimate zone. Since Ned is taller than most Chinese his nose is typically at their head level, and the olfactory input kicks in. He ends up smelling their hair.

The last time I played Pass the Orange was in my early teens, when it offered the tantalizing prospect of getting up close with a heart throb. On the chance that I might be missing something after all these years, I convinced Nick to demo a game in our kitchen. Sure enough, we immediately realized that the only way to get the orange was to throw ourselves in a deep embrace, but far from romance, we both recoiled at the thought of 1) doing this in public; and 2) even, worse, doing it with someone else. And then because they were in season, we tried to pass a Clementine, but that was even more difficult.

I cannot think of anyone that I would like to play pass the orange with in public, so I tried to think of who I would LEAST like to play with. In order to narrow the field down from every human being, I decided to identify my three most unappealing politicians, based on both personal and physical attributes. In no particular order they are:

1. Arnold Schwarzenegger

The Terminator gets a spot on the list because I find him so physically repulsive – I can only visualize him in his well-oiled body building phase, with an overeager and leering grim on his face. Additionally, a general rule of thumb should be never play pass the orange with someone with a zipper problem. I am nobody’s idea of a cougar, but why take any chances?

2. Richard Nixon

Physically unattractive is a no-brainer, but in addition the guy is so stiff and awkward, and his sallow complexion and five o’clock shadow in his debate with Kennedy are a lasting memory. If you are forced into playing pass the orange, you want someone who would try to make the best of a bad thing, not take themselves too seriously, and just get it over with. Don’t think that Tricky Dick could do it. After all, this was the man who strolled down the beach wearing a suit and wing tips.

3. Adolf Hitler

I knew that one of my picks would have to be a genocidal dictator, and sadly I have so many to choose from – Pol Pot, Josef Stalin, Slobodan Milosevic and any number of African despots. I choose Hitler because of the additional sensory input in the intimate zone. Adolf had well chronicled halitosis and chronic intestinal gas that could wilt a rose bush. He gets the nod as the worst of the worst.

The missing words in the following poem are anagrams (i.e. share the same letters like spot, post, stop) and the number of asterisks indicates the number of letters. One of the words will rhyme with either the previous or following line. Your job is to solve the missing words based on the above rules and the context of the poem. Scroll down for answers.

If you every have to play Pass the Orange here are a few ****

Make sure you play with someone who permanently zips.

And you might get plastered face to face with intimate strangers,

Exposure to sweat drips and stray **** are just two of the dangers.

Wait, there’s more! The final assault is the sense of smell,

Stinky arm**** and toxic halitosis will land you in olfactory hell.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Answers: tips, spit, pits

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: