Family Christmas Letter, 1963

“[Elizabeth] is in the 6th grade, no special interests, is good fun and pleasant company. Can’t really think of anything special to say about her…”

Family Christmas Letter, 1964

“[Elizabeth] is a Beatles fan, likes to work with a microscope and slices up animals – spreading frog and mudpuppy guts all over the kitchen and has a cherished cow’s eyeball and sheep’s heart in a tub of alcohol in her closet.”

Looks like I became more interesting in 1964. Yes, I did go through a phase of dissecting pickled mudpuppies that I bought at a very complete hobby shop, and animal hearts gathered from the butcher.

However, in my defense I would like to say that my mother embellished her description with her usual dramatic flair. No public kitchen display was involved. I shielded my family’s delicate sensibilities by confining my work to my bedroom. I prefer the scientific word “organs” rather than the gorier “guts,” and I take particular exception to the word “cherished.” Yes, I had an eyeball, yes, I stored it in a bucket. I do recall the humours in that eyeball, vitreous and aqueous suffused with the penetrating odor of formaldehyde, but no, I did not have an emotional attachment to the eyeball.

More intriguing is why my mother reported my peculiar hobby with such delight. This Christmas letter was sent to a vast network of family and friends, some close, many tenuous, who might have feared that this sweet 12-year-old was on a slippery slope towards an unhealthy relationship with roadkill. Why was my mother so excited for me?

Born in 1927, my mother grew up in an era of women with limited options. College was primarily a placeholder until marriage, with no expectation that women would have a professional career. She graduated in 1949, a few years after her older brother returned from WWII. Their father, my grandfather, set my uncle up as a stockbroker in his company. He slotted my bright and creative mother into a job as a secretary for one of his business friends. She met my father in the summer following graduation, was engaged by Christmas, and married the following March. Their first born, a son, arrived within the year, followed by a daughter (me) and four more sons. Her “career” as a secretary was quickly forgotten. On a bank form filled out to create a safety deposit box, she listed her occupation as “housewife.”

Even as a kid I sensed my mother’s frustration that society undervalued her talents. She wrote little ditties to sing at birthdays and family occasions. One memorable song included the lyrics, “What happened to the priceless, precious knowledge that I learned at Vassar college? All I do is wipe out sinks filled with spit and grit.” The chorus consisted of multiple rounds of the words “spit and grit.”

In an earlier Christmas letter she described me as a tomboy “through and through,” an identity she shared. My mother was the one who taught me how to throw a ball to save me from the humiliation of “throwing like a girl,” taught me the arcane rules of baseball like dropped third strike or the infield fly rule, so that I could compete equally with the boys. I climbed trees. I jumped off the roof of our house. My fingernails were dark with dirt. I didn’t play with dolls, and I only read Hardy Boy mysteries, never the companion Nancy Drew books. I was spunky and plucky, qualities she admired.

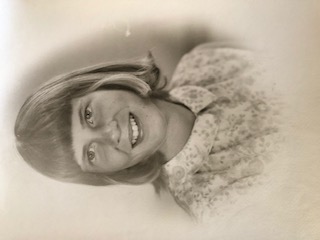

In the 1963 letter, she included an excited paragraph describing my older brother’s interest in radios and electronics. Perhaps she could see his future more clearly – not only wide open with a man’s options, but now my brother could march forward with a marketable talent. I was still a blank slate that year, and my mother might have sensed my uncertain future. As puberty approached, my socially acceptable rough and tumble days were drawing to a close. Society considered the spunk of a tomboy endearing in childhood, but adolescent girls were encouraged to shed that identity and become more feminine. My mother began to replace my unisex wardrobe with gender-specific clothes. I recall a floral print shirt with a demur Peter Pan collar, color coordinated with matching shorts. The zipper ran up the side of the shorts instead of in the front like all my other pants. Dancing school began in 1964 and my mother bought me a dress, stockings, and some sort of “party” shoes.

This was my slippery slope. How would I become feminine? Would I follow the expected path and develop an interest in sewing and fashion? Would I spend hours with hair and make up? Would I stop having boys as friends? Would I wait breathlessly for a boy to steal my hat at the winter skating rink, and wear a long tasseled hat just for that purpose? What were my mother’s hopes for me?

I had already shown early ambivalence toward the traditional path to motherhood. In my 1958 yearbook, our class was asked, “What would you like to be when you grow up.” I responded, “I guess I’ll be a mother,” perhaps spoken with a note of resignation.

Now, one year later, my mother sees me blossoming. My hobby may have been disquieting to many, but that was its charm. Her daughter’s spunky tomboy spirit wasn’t going to be sucked dry by cultural norms, she was going to dissect things and she wasn’t going to step aside and let the boys do all the fun stuff. My mother went all in on dissection. She drove me to the hobby shop, helped me order pickled animals from the science catalog and got the cow and sheep hearts from the butcher. I used them in a science fair exhibit of comparative hearts that was an absolute sensation. In 1964, on the cusp of women’s liberation, my mother sees opportunities for me, up in my room, wielding a knife, ready to puncture a cherished cow’s eyeball.

————-

[1] Fortunately, roadkill never held any appeal, but I did go on to a career as a pathologist, performing many autopsies and dissecting all sorts of body parts removed at surgery.

Follow Liza Blue on:

Share: