I recently took a walk alongside a herd of big-horned sheep in the Rio Grande valley north of Santa Fe, where I couldn’t help but notice tiny fecal pellets scattered all along the trail. How could such an enormous animal produce such diminutive scat, so different from the messy pies of their ungulate cousins, horses and cows? I decided to channel my hero, Charles Darwin, whose unfettered and determined curiosity about the natural world is my delusionally aspirational goal. Could I puzzle this out?

I have often imagined taking a walk with Darwin, wondering if we would go more than a few paces before he would stop to investigate a worm, a beetle, or a fecal pellet. After Darwin returned from his epic voyage, he spent 23 years before publishing the Origin of the Species, checking every odd specimen sent to him in order to ensure that our wondrous diversity could still be explained by natural selection. He needed his theory to be bullet-proof from his detractors, i.e., the church afficionados promoting intelligent design by some celestial sky daddy.

So surely he must have thought about pellets. The sheep must have a different intestinal design than the big splat herbivores, relying on rhythmically coordinated intestinal contractions to squeeze every drop of water out of the undigested bolus. The first question Darwin might consider was the evolutionary advantage of such an excremental strategy, and then work backwards from there to see if he could find evidence of intermediate forms. I rushed home to consult my “Origin of the Species.” No mention of feces, defecation, excrement, or anus in the chapter headings or index. However, at 686 pages, the 20-page index was woefully inadequate. A complete on-line copy of the book on Project Gutenberg allowed me to do a thorough word search. All key words came up negative, although I did find “anus” embedded in the word “manuscript.”

This seemed like a huge miss on Darwin’s part, not only the isolated example of the big horned sheep, whose limited access to water could explain the dry scat, but also the role of fecal management in the predator-prey relationship. Olfactory hunters, such as the big cats, follow their noses to track down prey. Animals use feces to mark their territory. Prey animals conceal their scat to throw off their predators. Such voluntary defecation among both predators and prey suggest higher brain functions are involved, along with the anatomic factors that allow animals to choose where and when.

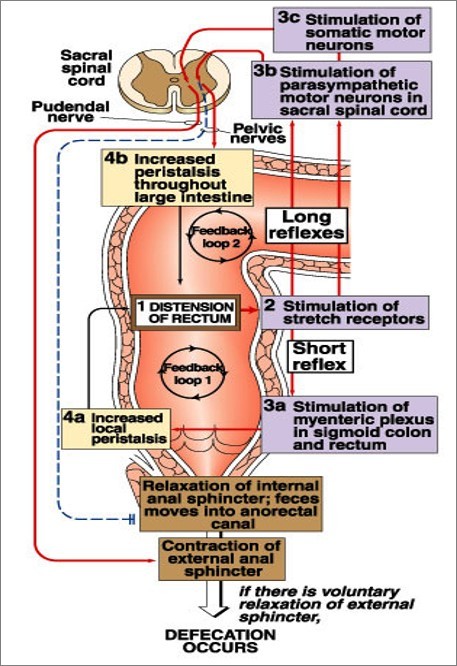

Diagrams of the anatomy and reflexes to control defecation look like a Rube Goldberg invention,[1] a tangle of nerves creating a delicate dance between inhibition and stimulation, involuntary and voluntary muscles taking their cues from each other. The whole operation is an evolutionary miracle essential to species survival.

In “The Origin of the Species,” Darwin studiously avoided any mention of human evolution for fear of the wrath of the church, but it couldn’t have been far from his mind. As humans evolved a bipedal gait, the anus migrated from the great outdoors to the deepest depths of the intergluteal cleft. Walking upright was a precursor to our handy opposable thumbs, but the new dank, dark location of the anus produced hygiene concerns, intensified by shared living quarters. Defecation became the provenance of the private sphere, creating a whole spectrum of psychosocial issues, including, but not limited to, an anal personality at one end of the spectrum and the joys of potty humor at the other.

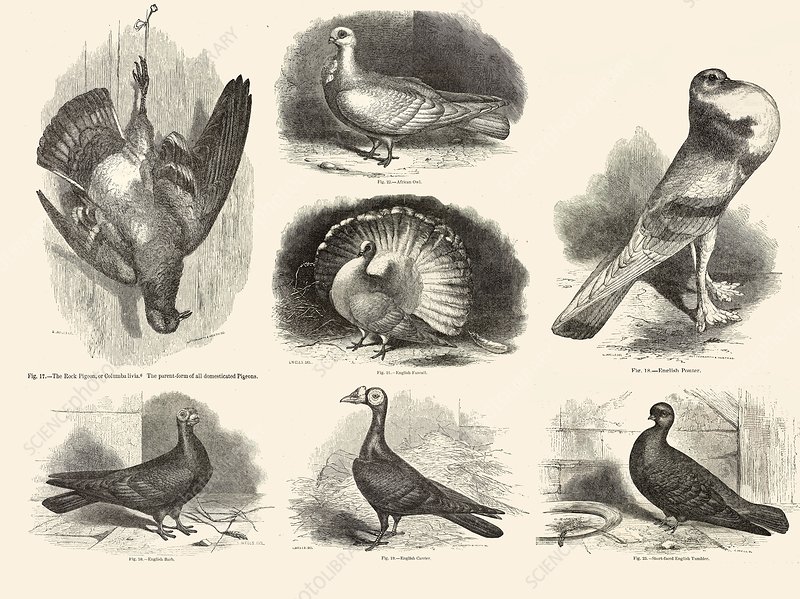

In 1871 Darwin gathered his courage to address human evolution and published his companion volume, “The Descent of Man. ” Here he focused on sexual selection as an evolutionary force. Evidence was all around him. As a pigeon fancier Darwin could directly see how deliberate breeding could produce wildly different appearances. Natural selection was an identical concept playing out over a longer period of time. A collection of his domestic pigeons, bred in his garden, are found in various museums.

The top picture shows a variety of Darwin’s pigeons. The bottom is an archived pigeon specimen with the original tag in Darwin’s handwriting. Various authors have credited his observations on pigeons as more influential to his theory of natural selection than his eponymous finches collected in the Galapagos.

The book describes the various “armaments” animals have evolved to demonstrate their physical prowess to drive sexual selection, and most visibly among birds, the role of beauty in sexual selection. Here is another of Darwin’s missed opportunities – the role of hygiene in sexual selection. The discerning female will seek out a partner who is sanitary and will not pass on fecally-transmitted parasites, a particular hazard among carnivores and blood imbibers. In fact, Darwin might have recognized this factor in his own marriage. In the forty years following his return to England, Darwin was plagued with a chronic illness that included nausea, vomiting, headaches and skin lesions. He was frequently bed ridden and able to work for only a few hours a day. The cause was never identified in his lifetime, but modern doctors, reviewing his diaries, have suggested that Chagas disease is a possible diagnosis. Chagas disease, common in South America, is caused by a parasite transmitted through the feces of a “kissing bug,” one of which was kept as a “pet” on the Beagle. This parasitic disease limited Darwin’s fitness and might have made his long-suffering wife reconsider her choice.

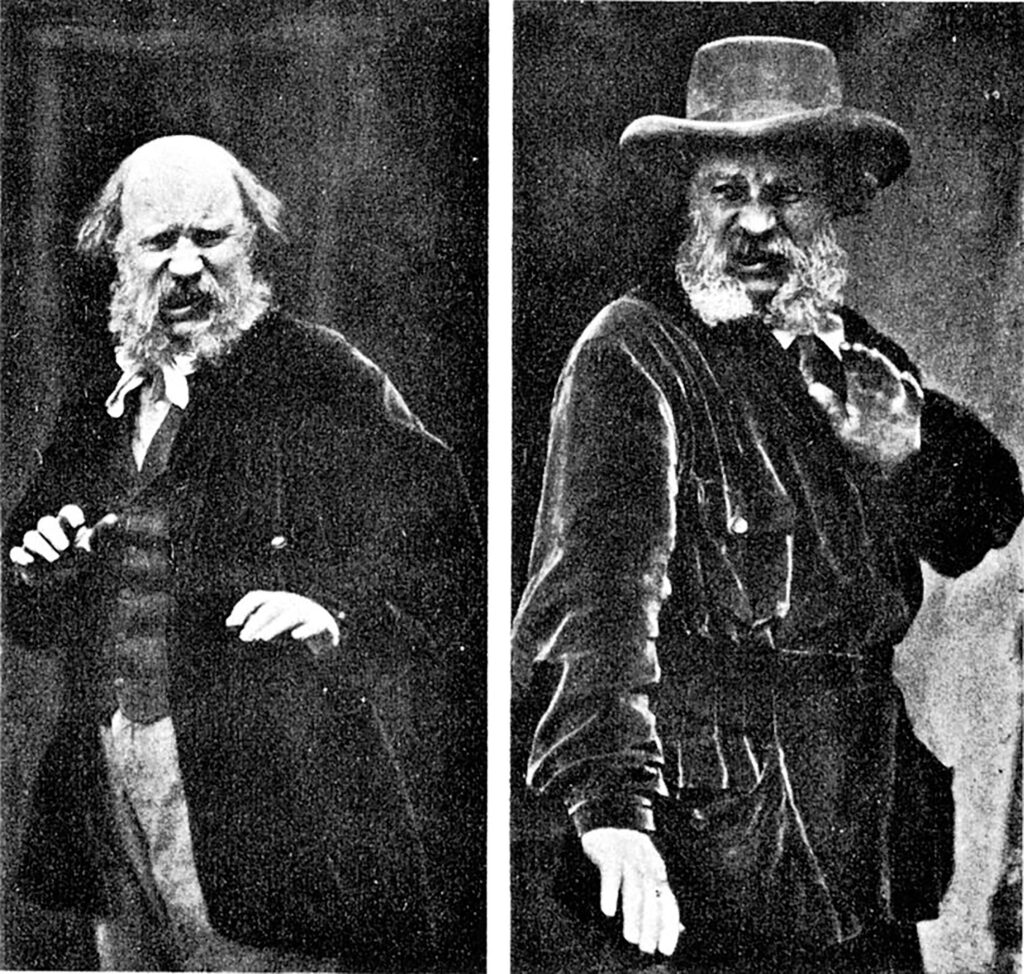

In 1899, Darwin published “The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals,” which provided descriptions of facial expressions. This was his first book to provide photographs, including one of disgust.

Darwin provided a detailed description of the tongue movements, facial musculature and nasal valves to produce the characteristic snorting. He comments that disgust is similarly expressed in both man and beast, suggesting an evolutionary role rather than a learned behavior.[2] Darwin does not take the final leap, noting that the evolution of human disgust and the accompanying avoidance reaction has protected us from the dangers of rotting food and feces.[3]

Am I crazy to think that I have glommed onto a useful framework to describe the anatomic, sexual selection, psychosocial factors that contribute to the survival of the fittest? Finally, a determined Internet search reveals a short 2013 article by two Italian authors, published in the obscure journal, Techniques in Coloproctology, titled, “The Control of Defecation in Humans: An Evolutionary Advantage?” The authors conclude, “Thus, the conscious recognition of the importance of controlling defecation may have represented a further weapon for early human beings, not only in the fight for survival, but also to improve hunting strategies and therefore to increase the evolutionary advantages.”

Darwin must have known this, but simply chose not to record this insight in his voluminous written work. He lived at the height of the staid and pious Victorian age, a culture that revered the human body as an unsullied temple. He did not need to descend into the unsavory depths of everyday life to showcase evolution when there were hundreds of palatable examples to choose from. He wrote at length about the uncanny (and some said God-given) ability of the bee to make a perfect hexagonal hive and waxed poetically on the beak of the shoveler duck, “whose beak is a more beautiful and complex structure than the mouth of the whale.”

I like to envision my walk with an elderly Darwin, perhaps holding his bony elbow as we take his habitual and contemplative walk along his sand path. I might gently broach my pet subject by praising the vast scope of his research, but also suggest that natural selection is so pervasive that additional evolutionary levers could be at play. Darwin might look at me quizzically, and in that small pause, I might whisper, “defecation.” Darwin would stop suddenly, grab both of my forearms, and say, “Yes exactly, finally someone who is willing to talk about this.”

We excitedly exchange our ideas as we walk back towards his greenhouse. Tea is approaching and I do not want to take more of his time. As I leave, he again grabs my arms and says, “I have never felt comfortable about addressing such a distasteful subject, so I am most grateful that you have taken the initiative. Here is my gift, a basic truth I will share with you alone. I will claim no ownership as I do not want to besmirch my reputation. But you might find it useful. Do what you wish with it. Become famous if you dare. These six words say it all.

“You cannot shit where you live.”

Darwin chuckles as he heads into his porch where his wife waits for him.

[1] A Rube Goldberg invention essentially uses the tools at hand to create an overly complicated invention. In fact, this is similar in concept to evolution where existing mechanisms are multi-tasked to other purposes, producing a serviceable, though not the most efficient design.

[2] Darwin describes the facial expression of various tribes around the world, which he unfortunately refers to as “savages.”

[3] Darwin wrote, “The most common method of expressing contempt is by movements about the nose, or round the mouth; but the latter movements, when strongly pronounced, indicate disgust. The nose may be slightly turned up, which apparently follows from the turning up of the upper lip; or the movement may be abbreviated into the mere wrinkling of the nose. The nose is often slightly contracted, so as partly to close the passage; and this is commonly accompanied by a slight snort or expiration.”

Follow Liza Blue on:Share: